The quest continues with our Rock Climbing Training Manual routine this spring. One interesting thing (among many) that has come to mind in the process of reading this book is the connections between effort, perceived effort, training volume and ultimately improvement. As I warmed up for my second hangboard workout of our strength phase I noticed a familiar yet somewhat foreign feeling of a deep forearm pump and slight aching in my fingers. A feeling you can only get after a really hard day of climbing or training. I then realized I haven’t felt that in a long time! I remember in the exciting first few years of climbing at the New River Gorge in West Virginia I could barely type after a weekend of hard climbing. I was sending some routes – sure – but I was also climbing a much larger volume of pitches each day as well as harder pitches that really pushed the limits of my finger and forearm strength. Concurrently I was progressing at a fast rate. Climbing the grade ladder partly due to the gung-ho enthusiasm to climb a lot but also due to learning invaluable skills along the way.

Some of the good ol’ days at the New River Gorge. Hiking into a shady crag in the snow? No prob. October, 2010.

What’s interesting is that after I became a bit “smarter” with my climbing evidenced by better technique, resting, pacing my crag days, etc. I also lost something important; good old fashioned ass-whooping days at the crag. It seems that each day at the crag became planned, warm-up here, move to this grade, rest then try projects. And sure I might be tired at the end of the day, but I didn’t want to get too thrashed because I would need energy for a send-go the next day right?

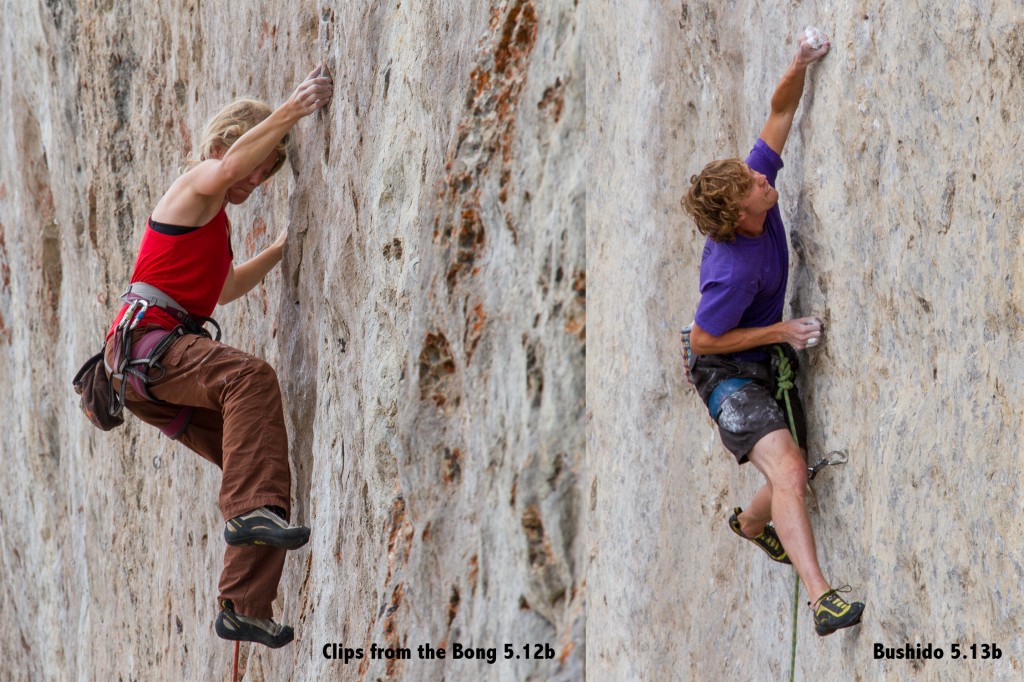

Robyn and I feeling about as strong as ever and dispatching some of our hardest routes on the same day. At this point I think both of us could have gotten on something even harder. The Fins, ID. July, 2013.

I may have trained hard in the past for short periods of time, and seen great results, but my limited scope of the greater picture of continuous improvement saw me jumping on the opportunity to get instant gratification with decent sends in the near term, and letting the training fall aside. What I saw happen, last year and the year prior, is that I would have a great spring and a relatively “flat” summer and by fall it seemed I had regressed even. Correlate that with the training for those two seasons, intense late winter and spring training, then coasting and getting more mileage on outdoor climbs in the summer, and it’s easy to see that a lack of intense days during the summer translated to an eventual lack of progression in the fall. All the while, when I was likely the strongest (spring and early summer) I had it in my head that I was going to coast, and wait to get involved with projects until prime weather in the fall. Then fall comes and I am employing siege tactics on my projects but I have completely missed out on my performance peak. A better method seems to be more staggered. Hop on some projects or potential projects when I am near my peak, but if they don’t go within a few days let them be and return at the end of the next performance peak to try again. Simple as it sounds, the “training” I have done in the past was much less structured around peak performance cycles and I essentially blindly followed workouts from a magazine. With a better understanding of why, how long, and when I should do my workouts I can better tailor the program to the results I want to see. So while my effort on projects in the summer and fall of last year seemed high, I would spend most of my time on easy terrain, and then get a few burns on the project. Many times it was a stopper crux. So the majority of my day hinged around one move. If you can do it sweet, you send, but if you can’t there is only so much beta you can glean before it’s time to step back get stronger and return at another time.

Robyn on the hangboard. The pulley system allows you to hold on to smaller holds by decreasing your body weight. It’s also quantifiable so you can track your strength gains.

Knowing, based on the fatigue in my arms and fingers, that I had achieved a solid workout was a great feeling and surprisingly motivating in it’s own right. Pushing your body to the edge, healing and getting stronger and repeating. But unlike when Ben and I used to go to the gym in college to make our man boobs bigger, the gains in strength and technique in rock climbing unlock all sorts of new routes and physical and mental challenges. Ultimately, many of the hardest routes are also the most striking and beautiful faces of rock at the crag and getting a chance to enter their arena knowing I have the skills, ability and training to be there is an exciting prospect.